WHEN COWBOYS GO VIRAL… BY DESIGN

A case study of the viral social media phenomenon on the digital channels of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

Abstract

On 17 March 2020 a viral event occurred on across multiple social media platforms. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA would suddenly have an international audience eagerly following the museum’s moustachioed Head of Security as he took over the duty of social media management due to the lock down. This case study will follow his journey and look into the implications for content production as a practice.

Introduction

It’s no secret that digital channels and social media in particular have become one the most important means of communication for businesses and organisations (Quesenberry, 2015) and during the coronavirus pandemic that, arguably, became even more so. Because of the pandemic a new challenge emerged for museums in particular: to keep people engaged while they were unable to physically come and enjoy the venue. While many struggled to do this, one museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in the United states, found success when they enlisted the head of security to take over their social media platforms as he was one of the few people still allowed in the building. What followed was a viral social media event reaching around the globe with engagement coming from as far away as Ireland, Singapore and New Zealand.

This case study will focus on the social media activity of the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum (referred to as the Museum) with particular attention paid to the time when Head of Security Tim Tiller took on the additional duty of Social Media Management and made his first posts, analysing content and measuring engagement. The aim will be to decipher what made this media so engaging and spreadable, and whether anything can be learned and applied to digital marketing in general.

Bounding and Data Collection

Spatial: Mr Tiller was initially active on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram; the posts on these platforms were often nearly identical, with reactions and engagement following suit. The museum’s YouTube channel was a more recent addition to Tim’s activities with a post just before Christmas 2020. For these reasons, and the advanced search capabilities on the platform, the bulk of analysis was carried out on Twitter engagement.

Temporal: Particular attention is paid to the posts starting from 17th March 2020, when Tim became active, we follow his activity to the present. To accurately gauge the change in engagement we look at posts as far back as March 2019 to get as clear a picture as possible of engagement prior to the viral event.

Methodological:

Hard Data:

o Engagement was measured by the number of comments, favourites/likes and retweets/quoted posts.

o Number of followers before the viral event were offered by the Museum.

Soft data:

o in an effort to gain the clearest picture of what happened to create this viral/spreadable event we attempt to analyse the content of the posts and the comments themselves. As this is inherently subjective an effort is made to focus on exact quotes and not make leaps or assumptions when possible.

o Anecdotal evidence is offered via an interview with Seth Spillman, Head of Marketing; referred to as “Seth from Marketing” in posts by Mr. Tiller; also, newspaper and magazine articles from the time.

Setting the Scene

The Museum’s History

The Museum was founded in 1955 and bills itself as “America’s premier institution of Western history, art and culture” with an “internationally renowned collection” (National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum - Oklahoma City, OK, 2020). The museum is no stranger to digital audiences with Facebook, Twitter and YouTube accounts dating back to 2009, and an equally prolific Instagram account.

Historical Use of Social Media & Monitoring Activities

By 2019 the social media presence followed a particular pattern that developed over time: professional looking photos and images of exhibits, individual pieces in the collection, and of events and activities hosted by the museum. The apparent driving force behind the posts seems to be aimed at driving local foot traffic to the museum by promoting event’s and exhibits rather than engaging on the social media platforms. The voice was of the museum as a generic entity and the tone can be described as blandly energetic: matter of fact but using exclamation marks for emphasis.

Judging by the lack of attempt at engagement within the social media platform it appears that social media engagement and interactions are not something that they were measuring, monitoring or striving to increase. If anything, it appears to be an afterthought rather than a marketing tool. This assessment of their social media activity was later confirmed in the interview with Mr Spillman (Spillman, 2020).

Ethical & Privacy Concerns

There are few ethical or privacy concerns related to this case other than the fact that the social media accounts being a public forum may give some audience members pause before posting or prevent them from responding at all. Although the greater portion of privacy ethical responsibility lies with the social media giants, it would be wise for organisations such as this to be conscious of the engagement they are inviting their audience to take part in and the truthfulness of their messaging (White and Boatwright, 2020) as they are essentially engaging in surveillance capitalism through their use of these platforms.

Macro Environment

In an attempt to decern what precisely happened in this case, it’s important to look at the environmental factors and stressors that were taking place at the time. In the US and elsewhere in the English-speaking world 2020 was shaping up to be an especially difficult year with devastating wildfires in Australia, the UK withdrawing from the European Union, Trump’s impeachment trial, and it was an Election year in the US, to name a few top headlines. The novel corona virus and resulting Pandemic would surpass these stressors to create perhaps the biggest global event since World War II.

By March 2020 much of the world was in some form of lockdown, sitting at home with little to do, many turned to social media as a way to pass the time, (Drouin et al., 2020).

The Viral Event

Due to the pandemic, on 17 March 2020 the Museum did not open its doors and only the security team were permitted in the building. The head of security, Tim Tiller, was asked to take on the duty of Social Media Management. This would result in a massive spike in social media engagement. Figure 1 shows the engagement on the Museums Twitter account from 1 January 2020 through 31 July 2020.

Figure 1: Comments, Retweets, and Favourites on Twitter. 1/1/20-31/7/20 (@ncwhm, 2020a)

Reading the comments on Tim’s initial posts it’s clear that people were looking for a bit of escape from the bad news that was flooding their feed: “this is what the world needs now” is a common theme. By the end of March, the museum had a massive new following when compared to before. A Wall Street Journal article from March 30th reports that the museum’s twitter follower number spiked up to 268,000 a 2,637% increase (Crow, 2020). Looking at the data, the viral event can be said to be contained in Tim’s first post on 17 March 2020. With over 10,800 retweets/quote tweets it outstrips all other tweets by more than threefold, by that measure.

Figure 2: Comments, Retweets, Favourites on Twitter. 17/3/20-31/3/20 (@ncwhm, 2020a)

A common theme when retweeting and sharing was something along the lines of: “This is the best thing ever, you’ll thank me, read every tweet and START HERE!” or some variation of that, perhaps giving a bit more detail. Another common theme for retweets and for quoting that first tweet, was a simple thank you to Tim for being so positive and an invitation to join in the fun.

This marks a significant change in Audience. No longer is the audience necessarily local, or even interested in cowboy and western memorabilia. The draw is now, at least in part, Tim: his personality and his story.

Analysing the Content

From the Audience’s Perspective

As seen in the previous figures, the first two weeks’ worth of tweets saw by far the highest volume of interest. The following is a brief look at those first tweets:

Tim’s first post on all platforms was a simple introduction: giving us a face and a name, each post was signed: “Thanks, Tim” which became a tradition as people commented on the novelty of signing posts that way. Tim appears happy to be in on the joke.

Figure 3.(Tiller, 2020a)

Along with the face and the name, we suddenly hear a distinct voice: a real person, a novice learning the ropes of social in real time and the change in content was as dramatic as the change in numbers that went along with the new posting style.

In his second tweet we see Tim misunderstand what hashtags are and, judging by the comments, hilarity ensues. This is followed by another fumble in the form of a plea for twitter tips, immediately followed by and apology: “sorry, thought I was googling that. Thanks, Tim”

Figure 4 (Tiller, 2020b)

What follows appears to be Tim’s stream of consciousness and follows him throughout his days, checking on different parts of the museum and pointing out what interests him. There are occasional “dad jokes” which see a spike in popularity when compared to surrounding posts, humour is certainly laced throughout and appears to come very naturally to Tim. We see Tim post pictures of the selfie station at “Seth from marketing’s” request, he charmingly gets it wrong:

Figure 5 (Tiller, 2020c)

Figure 6 (Tiller, 2020c)

Early on there was also a post (figure 7) that gives an important look into Tim’s personality that received significant response. This post was on his second day manning the social media accounts and is an outlier when it comes to tone, but it is consistent with the goodness, or perhaps the innocence, in his nature that the audience seems very responsive to.

Figure 7 (Tiller, 2020b)

Tim also points out details that might easily be missed by taking series of photographs of a painting each a bit more zoomed in than the last. The photos and videos are not professional and occasionally they are a bit unclear, this is another departure from the style when compared to the posts before Tim came on the scene.

For the remainder of March, the audience continues seeing the museum through Tim’s eyes and focusing on what stands out to him. There is no call to action initially, simply a look at specific exhibits and areas in the museum that Tim feels like showing that day, always accompanied by a playful bit of a text and the sign off: “Thanks, Tim” and usually using the new audience created hashtag: #HashtagTheCowboy.

By the close of March, the story of this social media event had been picked up by popular American media including PEOPLE.com and the Wall Street Journal. Amusingly, the PEOPLE.com post mentions Tim’s name as Tim Send, an easy mistake, perhaps, since it appears to be how he signed his first Tweet (Boucher, 2020). It’s never explained but as his actual last name is Tiller, it’s possible that he was using voice to text and by saying “Send” he was attempting to post the tweet.

Pulling Back the Curtain

In the Wall Street Journal article, the curtain is pulled back a little and we learn that “Seth from marketing”, as he is referred to in Tim’s posts, has been approving tweets all along (Crow, 2020). It seems clear that although Tim was, in fact, a social media novice he was also very much in on the Joke and this was a bit of clever marketing, albeit perhaps accidental at first.

In an interview with Head of Marketing Seth Spillman more is revealed: according to Spillman this was all rather carefully orchestrated at the beginning of March they had hired a new Digital Content Manager that conceived and directed the campaign along with Spillman and the marketing team. Tim was heavily involved and did contribute to the posts significantly, especially after the lockdown, but the initial posts had been planned and were ready to roll out when lockdown took place (Spillman, 2020).

How things have Changed

Spillman commented on how the change in audience has affected their approach and voice: they now have to cater to a national and international audience as well as their local audience (Spillman, 2020). Oklahoma being a “solidly red state” or Trump country as some call it, they chose to passively address the politicisation of mask wearing by simply having masks in their posts, which also happen to be available for sale. They addressed the Black Lives Matter movement by observing Blackout Tuesday and the post in figure 8 on the following day. This post showed high engagement across all platforms.

Figure 8 (Tiller, 2020d)

It’s clear from looking at the posts, and Spillman confirms, that from March, audience reactions are being much more closely monitored and content is being adjusted accordingly (Spillman, 2020).

Success or Failure?

As seen in Figure 1 the amount of engagement steadily declines after the first massive spike, it seems clear by the comments that people were more interested in the fact that Tim was a novice learning the ropes of social media in a funny way than they were about Cowboys and western memorabilia. However, the campaign should still be considered a great success as the viral event reached an international audience including many that follow to this day; a common comment one can see on all platforms is a promise to visit in the future so it’s likely that this engagement will turn into revenue.

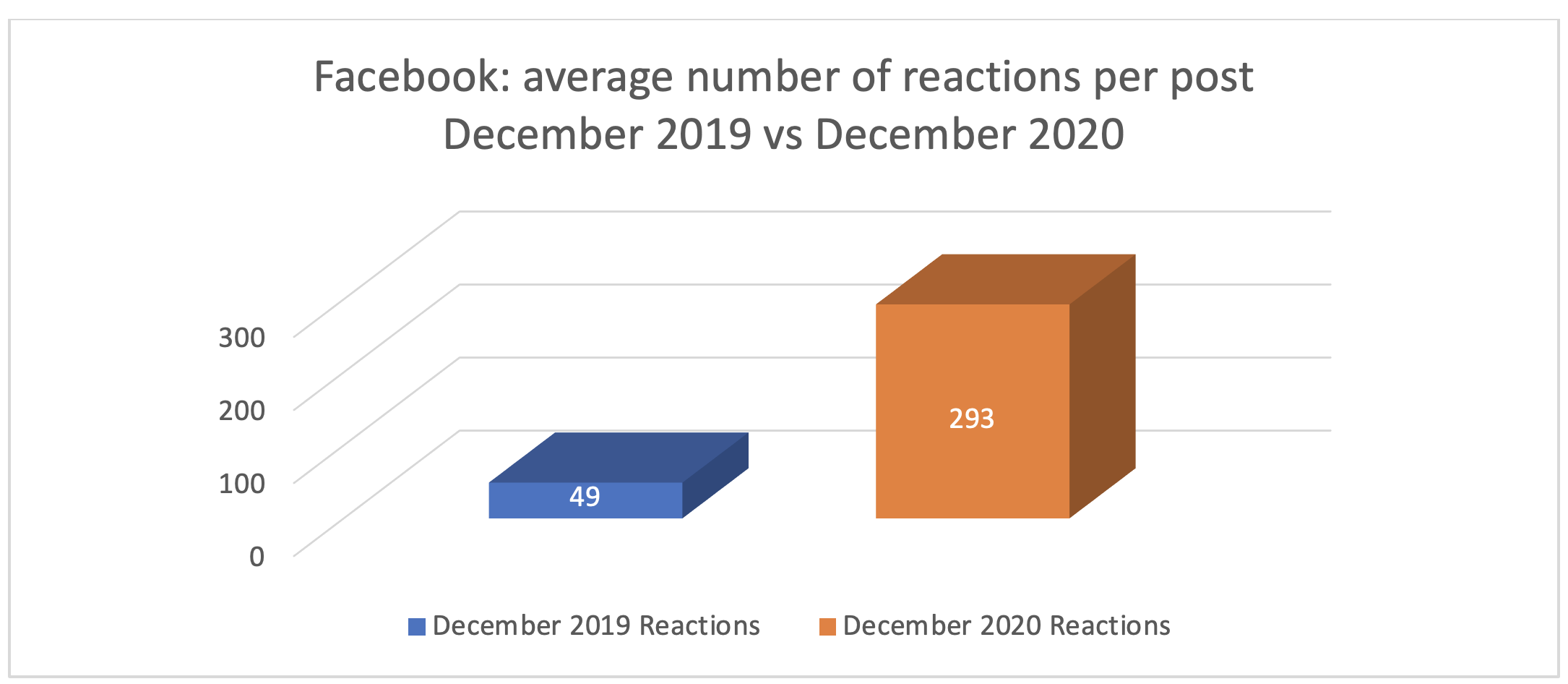

As the following figures show both followers and engagement across all platforms are up significantly.

Figure 9 (@nationalcowboymuseum, 2020)(@ncwhm, 2020b) (@ncwhm, 2020a)

Figure 10 (@nationalcowboymuseum, 2020)

Figure 11 (@ncwhm, 2020b)

Figure 12 (@ncwhm, 2020a)

The success in the campaign can also be measured by monetary gains. The museum sold out of the coffee cup that Tim featured in posts of his morning walks around the museum; they produced t-shirts with Tim’s new catch phrases “#HashtagTheCowboy “ and “Thanks, Tim” selling 500 in the first two days they were available; the museum also received donations attributed to Tim’s posts (Crow, 2020). Spillman reports that sales on Tim themed and related goods helped them meet previously set sales goals and continued to hold through the season Christmas (Spillman, 2020), some especially bundled together for the occasion.

As further proof that Tim is the key to the success of the campaign Figure 13 shows the spike in response that posts that include a selfie or photo of Tim receive.

Figure 13 (@ncwhm, 2020a)

Findings

Is replication possible? This question may be unanswerable, although it’s interesting to note that Disney Parks tried their own version in May 2020 with a member from the security teams of Disney Land and Disney World taking over the park’s Twitter accounts for the day (Disney Parks, 2020).

Figure 14 (Tiller, 2020e)

While exact recreation may not be possible there are potential lessons to be learned. Looking at Tim’s activities there are some key elements that may be worth noting:

1. He’s always positive and hopeful in his posts, never negative.

2. He tells a story: whether it’s talking about his favourite parts of the museum, meeting celebrity guests, or a contrived April fools’ prank, Tim draws the audience in by creating a narrative and telling a story, often with a beginning middle and end contained in separate posts.

3. He engages directly with the audience asking for feedback and responding to comments, creating connection and a conversation. This is a stark contrast to posts from before Tim’s time: he invites the social media audience to engage with him directly and seldom has a call of action around coming to the museum or spending money in their online store.

4. He uses humour and fun whenever possible, never seeming afraid to appear silly.

5. He shows himself and colleagues in photos.

6. He offers behind the scenes glimpses.

7. While he continues to feature individual pieces and exhibits as the museum did previously, he shows greater detail and adds playful commentary on why it interests him, making it more personal.

8. He comes across as just a “regular guy” and is easy to relate to.

9. Even though merchandise was produced rather than a “hard sell” with multiple links to their online store they take a more passive approach typically just showing rather than telling, product placement style.

Much of this is in line with traditional and new marketing techniques and follow accepted best practices in creating engaging viral and social media content. (Quesenberry, 2015) (Mohr, 2017) (Ryan, 2016)

Recommendations

There is one area that could be improved upon that could increase social media traffic, namely the use of hashtags and tagging. Although hashtags were a topic of discussion early on with his new audience, and a new hashtag was born as a result, #HashtagTheCowboy is nearly the only hashtag ever used and it is rare that individuals, artists or other businesses are tagged in posts.

Privacy and ethics may now become more of as an issue as well, with the newfound audience it would be wise to collect as much data as possible about the followers that engage the most in an effort to find look alike audience members not yet converted. With no real GDPR equivalent in the US this is less of an onerous task than it would be elsewhere; but keeping an eye on ethics, the museum could easily meet or exceed GDPR as data collected would focus on demographics, interests and behaviour while remaining non-personal or identifiable.

References

@ncwhm (2020a) Nat’l Cowboy Museum, Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/ncwhm/with_replies.

@ncwhm (2020b) National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum - Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/ncwhm.

Boucher, A. (2020) National Cowboy Museum ’ s Security Guard Takes Over Their Social Media Amid Coronavirus Outbreak, PEOPLE.com. Available at: https://people.com/human-interest/national-cowboy-museum-security-guard-takes-over-social-media-coronavirus-outbreak/ (Accessed: 17 December 2020).

Crow, K. (2020) ‘Meet the Museum Security Guard Who ’ s Now an Internet Sensation’, Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/meet-the-museum-security-guard-whos-now-an-internet-sensation-11585598395.

Disney Parks (2020) Follow Along with our Security Teams for a Peek Inside Walt Disney World and Disneyland Resorts | Disney Parks Blog. Available at: https://disneyparks.disney.go.com/blog/2020/05/follow-along-with-our-security-teams-for-a-peek-inside-walt-disney-world-and-disneyland-resorts/?CMP=SOC-DPFY20Q3wo050720200001G (Accessed: 29 December 2020).

Drouin, M. et al. (2020) ‘How Parents and Their Children Used Social Media and Technology at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associations with Anxiety’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(11), pp. 727–736. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0284.

Mohr, I. (2017) ‘Managing Buzz Marketing in the Digital Age’, Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness, 11(2), pp. 10–16.

National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum - Oklahoma City, OK (2020) nationalcowboymuseum.org. Available at: https://nationalcowboymuseum.org/ (Accessed: 19 December 2020).

nationalcowboymuseum (2020) National Cowboy Museum - Instagram.

Quesenberry, K. (2015) Social Media Strategy : Marketing and Advertising in the Consumer Revolution. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Ryan, D. (2016) Understanding digital marketing: marketing strategies for engaging the digital generation.Kogan Page.

Spillman, S. (2020) ‘Interviewed by Taylor Hooper on 30 December 2020’.

Tiller, T. (2020a) 17 March 2020. Available at: https://twitter.com/ncwhm/with_replies (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

Tiller, T. (2020b) 18 March 2020. Available at: https://twitter.com/ncwhm/with_replies (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

Tiller, T. (2020c) 19 March 2020. Available at: https://twitter.com/ncwhm/with_replies (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

Tiller, T. (2020d) 3 June 2020.

Tiller, T. (2020e) 7 May 2020. Available at: https://twitter.com/ncwhm/with_replies (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

White, C. L. and Boatwright, B. (2020) ‘Social media ethics in the data economy: Issues of social responsibility for using Facebook for public relations’, Public Relations Review, 46(5), p. 101980. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101980.